Our November 2023 BIPOC Foodways Alliance was co-hosted by Mecca + Sabrina. Through our deepening exploration of Nigerian food, we not only come closer to our ancestors, but each other.

Some words from Mecca:

“It doesn’t look like Africa, but it tastes like Africa.”

My Nigerian friend and colleague Uche Iroegbu gave me this feedback regarding my amateur West African cooking, the cooking that I hope and intend to make my own for the rest of my life.

It was a high compliment, because while I don’t expect my cooking to look like African cooking– I take liberties with plating technique and ingredient ratios– I do very much hope it will in some way conjure the motherland.

“The motherland.” Such a funny phrase. We all know what it means– for Black people, it means Africa. But what does the average Black American really know of Africa? In all my life, I was taught very little, if anything.

I knew that the slave trade originated there. Itself an untruth– the slave trade originated in Portugal and Britain. I knew the phrase “deepest, darkest Africa.” Itself a racist mantra that means nothing at all except that we were apparently expected to think of Africa as something to be thought of as unknowable, as something to fear. I felt none connection to the place. When I had an opportunity to go in my early twenties, I wasn’t even interested. I made no effort whatsoever to go. I was as disconnected to what was purportedly my motherland as any random, faraway dot on a globe.

But then one day I got a DNA kit– now about as ubiquitous as a box of condoms on a drugstore shelf– and spit into the test tube with some amount of nervous anticipation. Several weeks later, I was suddenly part Nigerian, a fact I could have never known previous to this gift from the gods of technology.

Still, at 50 years old, what do I know of Nigeria?

Almost nothing, still. I know more about European countries I have never set foot in than I do my own DNA. Even if I set forth on a course to learn, I’ll never likely truly feel Nigerian. The American project made certain of this, currently trying to seal the deal with a fresh infusion of white supremacy, circa 2024.

But while the identity I received in that report was, is, and will likely always remain nebulous, from it I also received an extraordinary gift: family.

My niece Sabrina is the 29-year-old daughter of my brother Lonnie, who I have yet to meet in person. There’s a sister too, named Rebecca (birth name Cynda), and her grown son. Lonnie has two other kids, neither of whom have I met. But Sabrina, thus far, is my prize.

There’s a semblance between us– maybe not striking, but it’s there. She notices mannerism similarities; I don’t really but maybe that’s because I’m not overly self-aware of what I look like moving through the world. But more unique than those things is the immediate familial connection where it took no time at all to get to know each other and I’m afraid I’ll have to use the cliche adage that I feel like I’ve known her forever. We look like family, and we feel like it too.

Like me, Sabrina was raised by the white side of her family. Like me, she did not and could not have known her paternal grandparents, much less her great-great grandparents.

I don’t have to tell you that if you’re Black in this country, what you probably know about your genealogy stops a couple of generations ago. You might know your great grandparents, but what about their parents? The first census that included the names of most African Americans was the 1870 U.S. Federal Census. Before this, records of Black births were rarely kept outside of some enslaver’s family bible.

My Norwegian great grandmother Myrtle Lilleskov was born in 1899. If she were born Black, she would have only escaped slavery by less than 45 years. This means that my great-great grandmother (and grandfather) on my father’s side was very more than likely enslaved during some portion of her life.

This context feels very important to me because it punctuates that slavery was 1. Not a long, long time ago, the way that this country likes to have us believe and 2. That my familial ties to enslaved people are extremely close– too close. It makes sepia tattered photos in history books seem real. Too real.

For 12 generations Africans were enslaved in this country. Sabrina and I cannot know when and how our ancestors arrived on this soil, but arrive they did, and now we are here because of it. Ain’t that something?

We have a tendency to gloss over that history in this country, acting as though the extraordinary presence of “African Americans” is no big deal. Or worse, that our presence carries with it some sort of inherent shame, which perhaps it does, but it is not Black people who should be carrying it.

When someone mentions the phrase “holocaust survivor” in this country, it is meant to mean something unimaginable, and we are collectively meant to take a pause and be reverent. I take no issue with this, but as African Americans, we are all survivors of a kind of holocaust, too: an ethnocide: “The deliberate and systematic destruction of the culture of an ethnic group.” Not a systemic extermination of our bodies– though that was true in many cases too– but a systematic extermination of our humanity. Our bodies' only worth was in forced labor and breeding for more forced labor.

It’s only a function of white supremacy that as descendants of survivors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade we don’t enjoy all of the reverence that should go along with this status. Our survival at all is quite literally against all odds.

My status as a Nigerian American (of sorts) offers me more than just an Indigenous country to name. It offers me a culture more grand, more stately, more dignified than that of being American. It allows me to be much more than just a descendant of slaves, the way this place would have me believe– the way it tarnishes even that astonishing fact with disrespect.

As a chef, my entry point to Nigeria is food. When I make egusi, I don’t pound the bitter melon seeds in a mortar and pestle the way my ancestors might have. I puree them in a food processor like any American interested in speed and efficiency. I toast them in a pan and I combine them with many roasted red peppers, onion, garlic, tomato and habanero pepper that I have simmered in the astonishing earth and flower of Palm Oil. I fold chiffonade Collard Greens into the mix and allow them to wilt that way, rather than slow cook. I serve the whole of it over charred sweet potatoes. Everyone who tastes it wants more. I had a guest say she wanted to eat it for dessert.

Sabrina and I would likely have never had the pleasure of tasting this food before I picked up some cookbooks and began acquainting myself with the African section of my local global market. We would have likely never known a thing about egusi– this breathtaking dish that tastes like nothing else– were it not for that DNA kit. And, more important than any of that, we would not have known each other.

A vial, hardly larger than a travel sized tube of toothpaste, changed the trajectory of my life.

What I truly know about Nigeria could likely fit into my egusi pot. But there are entire worlds inside.

Worlds that taste like Africa.

Some words from Sabrina:

When I sit down to write about how my aunt Mecca and I met, it feels overwhelming. How can I possibly describe the person who is now my closest family member—and the unbelievable story of how we met—in a short post for Substack?

I can’t. It’s not possible. So for now, I’ll give you the SparkNotes version, and then I’ll tell you about my “new” aunt’s African peanut stew—and why it tastes like the feeling you get when you’re at home.

Because my dad was adopted, I didn’t grow up knowing much about my paternal ancestry, and I could never answer the commonly asked questions about why I was so tan, why my hair was so textured with curls, etc. And, thanks to the adoption separating my dad from his people, I didn’t grow up knowing about my dad’s biological siblings—including his sister, Mecca Bos, my aunt.

Mecca and I connected back in 2021, following my comment on her Facebook post, “I know this is weird, but... I think you’re my aunt!” Later, she went out and bought an Ancestry DNA kit to confirm what we already knew from our strikingly similar passions and characteristics—she was, in fact, my dad’s sister.

Our connection itself could be the topic of an entire post. I’ll say the cliche here, because the shoe fits: it feels like Mecca and I have known each other our entire lives. And, the DNA is quite astonishing to me. Like, sometimes when Mecca tells a story, she emphatically moves her hands in a way that brings me back to seeing my own father’s mannerisms and gestures—the same ones that I sometimes recognize in myself.

Fast-forward to 2024: who knew Mecca and I would join forces to start a nonprofit organization to dismantle white supremacy?

At our recent BIPOC Foodways Alliance Table, Mecca made an African peanut stew. Peanut stew is really common in African cooking. But, if it weren’t for Mecca, I honestly don’t know if I would have ever known that—nor would I have tasted this and other foods of our heritage.

When I first tasted that soup, I literally said “Wow” out loud. Few things impress my taste buds these days—a consequence of losing both my taste and smell to that early-2020 variant of COVID-19. But this soup... Damn.

Before Mecca’s peanut stew, I can’t remember the last time I took a bite of something and actually stopped to think about the flavors I was tasting. When I took the first bite of that African stew, I felt a desire to slow down and appreciate its warmth and rich nutty taste.

From the first taste, I couldn’t get enough of that soup. And, somehow—even though I had never tasted it before that moment—it seemed oddly familiar. Part of me wonders, is that because African peanut stew is one of our family’s heritage foods? After all, it’s a recipe that traces back to the land of our ancestors…

It sounds weird, but I think my soul has always tried to tell me when I’m home—specifically, in moments when I’m embodying the heritage of my ancestors.

Long before learning about our family’s West African lineage—and finally getting some answers to life-long FAQs (i.e., “What are you?”)—I believe my soul first felt a connection to my heritage via tapping into my community’s need for social justice.

Even as a little kid, I felt a strong desire to advocate for equality. Once, as a 9-year-old, I sat my family down during our annual summer trip to the cabin and declared that—upon our return home—I’d be going to Valley Fair to protest racism and discrimination from the tops of the rollercoasters.

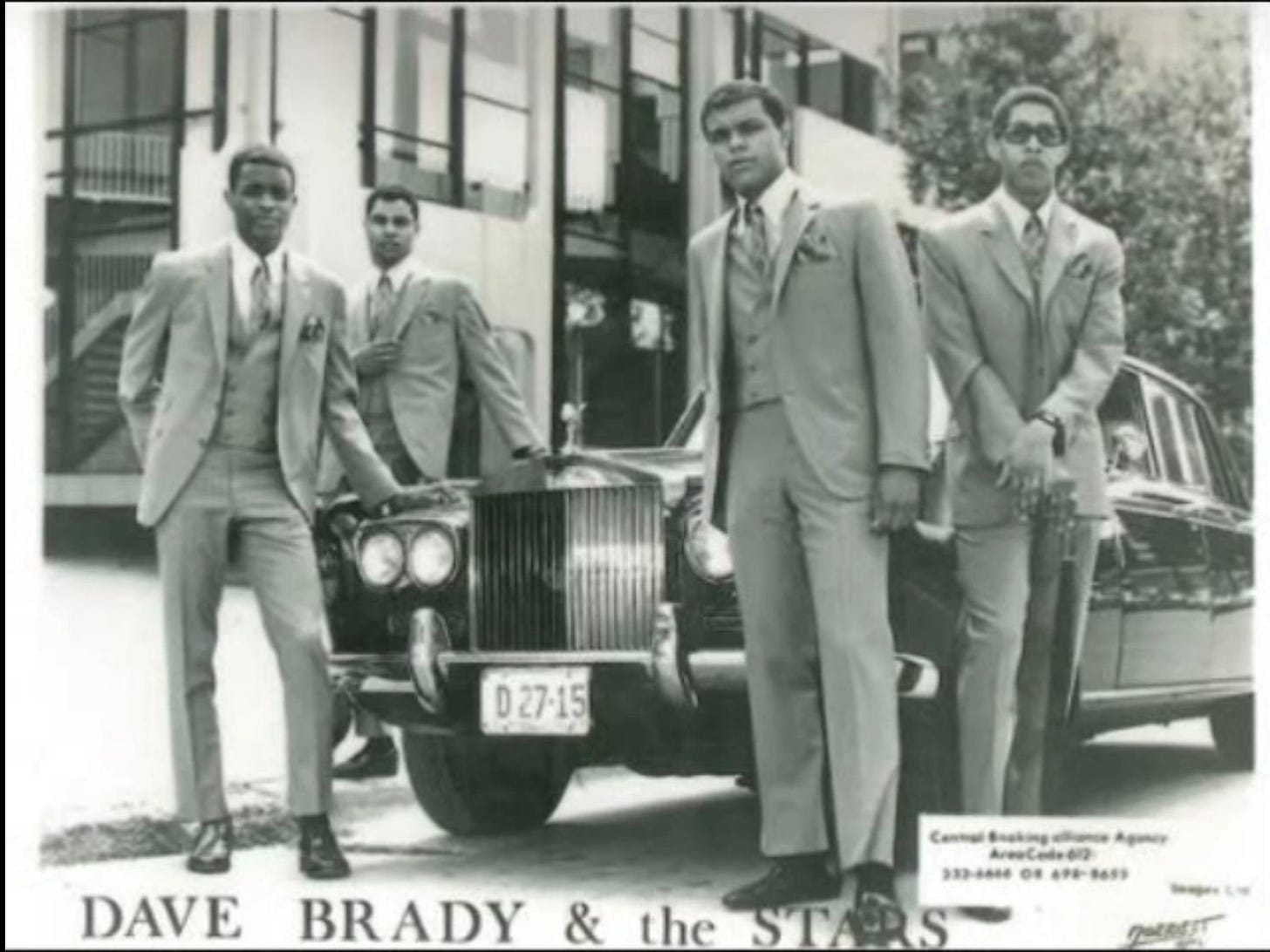

Later, at 16, I stood in front of the producers at my American Idol audition, proudly singing “A Change is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke—the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. At the time, I didn’t know what I know now: my grandfather—Mecca’s father—was the lead singer of the first interracial R&B band in Minneapolis, Dave Brady and The Stars.

Activism and music were two things that always gave me a connection to something bigger than myself. Now, I know: these were two avenues through which I could tap into the legacy of my ancestors.

Tasting Mecca’s African stew was another moment that my body in the present felt as though it was connecting to a distant memory of the past. Like, once again, my soul was telling me, “You’re home.”

This time—with more knowledge about my heritage—I’m confident that the fulfillment and wholeness that came with each bite of soup was from a deeper place. Like, maybe somewhere in my DNA, there’s a memory of African stew from an ancestor…

As she stirred the pot of soup, Mecca said, “I certainly don’t know a lot, and that’s not my fault.”

And she’s absolutely right. Africans forcibly deposited in Virginia in 1619 marked the beginning of Black communities in America being stripped of our generational wealth for centuries to come. I’m not talking about financial wealth—although that’s obviously a huge part of it, too. Here, I’m talking about wealth in terms of knowledge and access—knowledge of and access to our culture, ancestors, and histories.

Finding my aunt Mecca has helped me to heal our family’s generational trauma of disconnection; through reconnection, our family is boldly reclaiming our roots. Together, we’ve explored our West African heritage through cooking. (Well, Mecca mostly does the cooking—but I’m always down for the tasting).

As Mecca has started exploring her identity as a chef through our West African heritage foods, we’ve had the pleasure of learning more about Nigerian foods—like egusi and Red Red Stew—from our friend Uche Iroegbu.

When Uche talks to us about Nigeria, he calls it “our Nigeria.” His words feel like a warm, welcoming embrace—his use of language serving as a gentle reminder of “our” belonging to the land and culture.

At our BIPOC Foodways Alliance Table, I told Uche that one of my best friends from high school—Onye—is also Nigerian. Coincidentally, like Uche, Onye is from the Igbo tribe—just like Mecca and my ancestors would be today.

Uche said he doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that I ended up hanging out with another Nigerian girl years before I knew my ancestors were Nigerian. We find each other—we find our people and our culture—and that’s not by chance. Our souls long for where we come from. Our souls tell us when we have connected to our home.

When I tasted Mecca’s African peanut stew, my soul was getting a taste of where I come from.

My soul was reminding me: “Sis, this is home. This is our Nigeria.”