In Conversation with Michael Shaikh

Author of The Last Sweet Bite on the destruction of culture, building community, and how eating together may be the thing that saves us

Our September Immigrant Kitchen was a departure from our regular programming: we had a man in the house!

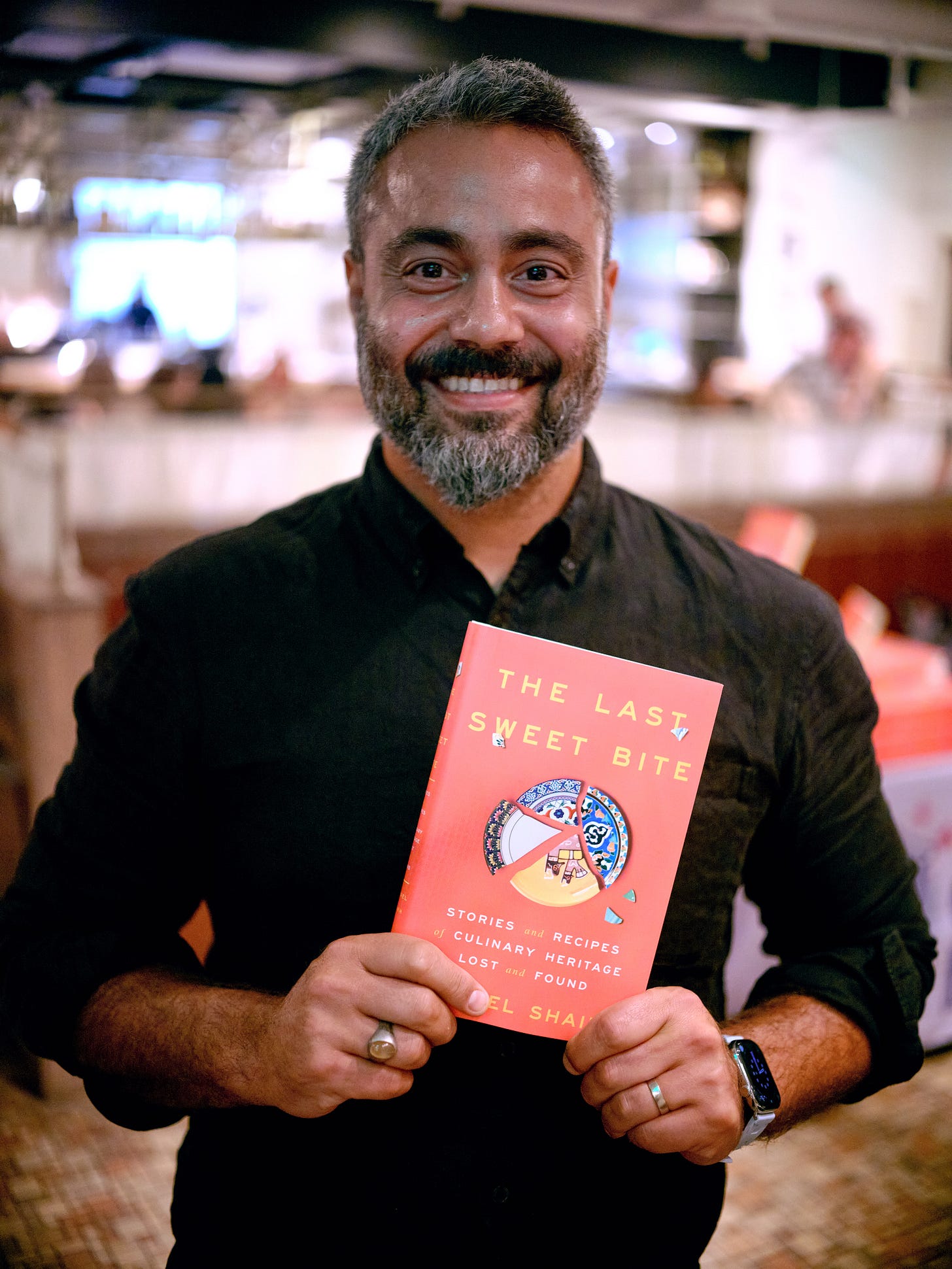

Not just any man, but Michael Shaikh, human rights investigator and author of The Last Sweet Bite, a powerful exploration of cuisine in conflict zones. The book highlights the persistence of people struggling to protect their food culture in the face of war, genocide, and violence.

Michael generously flew to Minneapolis from his home in New York City, joining our Immigrant Kitchen cook Alyssa Saleem, pastor and human rights activist (who we will hear from later) to present a Pakistan Street Food menu that the two collaborated on showcasing their shared Pakistani identity.

It was an incredible evening highlighting how food intersects with community— true community being what Alyssa misses most as a new transplant to Minnesota, and community being the thing that Michael leans into when work makes life difficult.

A conversation with Michael:

Mecca: Thank you so much for writing this book. I want to lean into the theme of community that we zoned in on at the event. I really liked what your wife, Dominique, told me about your way of keeping your mental health in tact as you talk to people in your work as a human rights investigator about the worst moments of their life. She said that you stay balanced by building different communities, all over the world. Can you say more about this?

Michael: I really do try to keep good people close wherever I go. I mean, it’s kind of the nature of the work. When you’re interviewing people, you do have to build their trust. I’m genuinely interested in people, and what they have to say, and and you do end up building a relationship. A camaraderie and a friendship with people through it— and I like to keep them close.

Mecca: This is how you keep yourself healthy, even in the face of war zones?

Michael: I’m generally an optimistic person. I tend to see the best of people. And one of the reasons why I actually do this work, if I just break it down, is that I’ve always been intensely, intensely interested in human beings, and I wanted to go to places where I could see the best and worst of us, in real time.

And I don’t know how, but I was kind of drawn to conflicts. I really got to see the mentalities of people who were fighting and while they’re fighting, they weren’t villains, right? You know, people were doing villainous things, but the people fighting weren’t villains themselves. Often, they were trying to fight for something to protect their own people, or a lofty political goal. And so it showed me that conflict brings out the best and worst of humanity. I’m just drawn to these stories of persistence and resilience and defiance, and those kind of people are magnetic— you build connections with them, and you want to keep them around.

So I have built a lot of different little communities across the world and in different places, and I try to bring them together as much as I can. It makes the world more interesting to me, and it also keeps me in check. It keeps eyeballs on me. Like, I think the greater accountability I have, the better person I am.

Mecca: The United States is in a political space that is pushing us away from community building, and then when you toss in technology, the pandemic, etc., how do you feel about all of the isolation that you see in this country? Is there hope for us?

Michael: Western capitalist societies in America are kind of extreme in this way— we have atomized families. We don’t live multi-generationally. Whereas in a lot of other places that I’ve worked have the opposite kind of culture. Pakistanis and Sindhis live multi generationally. My sister-in-law, who’s Japanese— they live multi-generationally in the same homes, right? And so you have these big extended families we don’t have. I grew up with a very nuclear family— mother, father, brother, sister. We didn’t have very much extended family, but my mom really wanted us to have a big family, and she went out and knitted one together. She kind of built it from scratch and over the past 50 years of my life, our tables and holidays keep getting bigger and bigger and bigger. There’s more chairs, there’s more kids.

Because this is kind of unique to America, the way we are here. We talk about having this melting pot, right, or this tapestry in this country, and I don’t necessarily think that’s true. I think there are elements of it, but our communities are ghettoized, right? We separate ourselves from each other— racially, economically. “Were you born here? Are you an immigrant?” You have all of these fulcrums in which the United States’ culture and society hinges on, and at the heart of it, it’s all about separation.

And you throw social media on top it— this thing that is meant to divide, and not bring together. I think we are now in a realm where the US is losing its grip on community. At the same time, though, there are people like you, right, that do see value of community, and you are doing these things like Immigrant Kitchen that is bringing people together, and you’re turning people away at the door because they want to come. So I think you have a society that is moving hastily in one direction that is fractured and divided— but at the same time, you have this real desire to have more community. So that keeps me optimistic.

I do think that human interaction and contact is important, and I think we are recognizing this. We’re starting to have better conversations around division. There are inklings of better, more meaningful conversations. They’re not national ones yet, but we are seeing them bubble up. So I hope that we will grab onto these things. But you know, equally, I am very worried about us not being able to talk to each other anymore, not being able to embrace the colors of America’s communities. I’m trying to be optimistic, and I’m worried. I see things like Immigrant Kitchen here in New York, and other cities— there is this desire to be more connected. I think we just have to find a way to facilitate these connections. And we need our politicians to help us and do this too.

Mecca: Yes, whenever I leave our events, I feel so lifted up— I feel like, “Oh, this is how it really is.” You know, people really do want this, they they get so much out of it, and they feel so full afterwards. I have people rushing up to me telling me how much they got out of it, how meaningful, and this is exactly what they need, etc. And then I leave there, and I switch on the news, and I feel like, is that how it really is? So Michael, what do you think? Do you think people are inherently good or inherently bad? Or is that too binary?

Michael: I tend to find the best of people until I can’t anymore. Okay— I tend to look for it. Maybe I give people too much of an opportunity, and maybe I shouldn’t, but it’s just the way that I’m built. But just because I try my best to find a redeeming quality in someone, doesn’t mean that I always have to agree with them. I mean, there are people that I’m sure have redeeming qualities that don’t like. There are a lot of war criminals I’ve investigated or I’ve interviewed in my life, and I gotta tell you, sometimes they can be charming, but they are criminals. That’s an extreme— they’re on the outer edge. But like I said, I tend to search for the best in people until I can’t anymore.

Mecca: It sounds like you have hope.

Michael: I do. I do have hope. And I have to say, this brings us back to food in some ways, Like, before I started writing this book, food had always been important to me, right? We talk about how important it is and how it brings community together. And, you know, I read about that stuff, and I heard people say it a lot. It always sounded kind of gimmicky to me, and cliche, and I dismissed it for a while.

But I had some of these experiences in Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, people whose food cultures were disappearing, and they shared with me family recipes and how important and profound these things were to them. It really opened my eyes to how important food was, and in those moments, I began to see the truth and the power of food, not only to tell a story, but to bring community together, right? To bring a diverse set of people together and show us what’s possible like in these moments of intimacy and empathy over a meal, right? And I think, we have to use tools like this.

In the moment that we’re living in, and the fact that we are, as an American society, suspicious of one another now in a way that we may have not in my lifetime, right? That I haven’t felt. How we’re willing to draw a line so quickly between ‘us and them’ based on how we voted in one election, right? How I want to approach that is— food is something that’s common to all of us. And if there’s a way to use that, to even employ that a little bit, to have a conversation with people to start dissolving the red and blue that divides us. We don’t always have to agree, but just to take the vitriol and violence out of our conversations. Right now, I think that’s the best we can ask for, and I think food allows for that, right?

Mecca: Sometimes I’m afraid I’m preaching to the choir. Like, sometimes I’m worried, like, oh, are we just talking to, you know, the public radio crowd, who would be here anyway? So I’m hoping that there’s people in the room who maybe when they leave, they’ll take something away that they didn’t know before.

Michael: Right at the heart of all this is discomfort. I think we have to be uncomfortable in having conversations with people we don’t agree with, going into places we may not always be welcome in because of our skin, and we one-hundred percent have to have these conversations. We’ve become a bit too precious. We don’t want to be offended. But we should want to hear things that make us uncomfortable, and we should want to have conversations with people where it’ll be uncomfortable but respectful, right? We’ve kind of lost that a little bit. We need to work to create a better community, and part of that is being uncomfortable at times, if not a lot of the times, right?

Mecca: You’ve obviously lived a very big life, very big career. You’ve obviously already done a lot of this work, but what do you know now that you didn’t know before you wrote this book? In other words, what is your takeaway after having written this book about the world and about the work you do?

Michael: My work investing human rights abuses mostly in war zones was basically investigating the consequences of governments beating up on their own people. And what I didn’t really understand was the extent to which governments, the powerful, really understand their enemy’s culinary culture. They will study it vociferously, intensively, in order to undermine it, in order to erase their enemy. And I did not see that at all. It never really occurred to me until I started researching this book— attacks on culture— food culture— can presage attacks on people. Physical attacks. So I think we have to be watching out for that. I mean, this is nothing new history. Historians have talked about it. You know, Sean Sherman’s entire people have understood this since the beginning, right, that food is used to erase people. But watching out for that now in contemporary times, and contemporary wars and violence— we might be able to prevent some of the worst things from happening.

Because in almost all cases, destruction of food culture involves land theft and forcing people from their ancestral homes. It’s important to start with the fact that at the heart of many cultures is the belief that people are part of their ecosystem, not separate from it. Food binds people to their land, and these two things bind people to one another.

Food is far more than just basic sustenance, the daily accumulation of enough calories to keep a person alive. What and how we eat are central to human culture. There are recipes, written and oral. Specific ways of organizing, cooking, serving, and eating meals. Ingredients and flavor profiles. Even the structures, like homes and kitchens, and the societal infrastructure, like bakeries, farms, fishmongers, masalawalas, and seed savers, that enable a food culture are almost always connected to specific geographies of a people.

This type of violence basically forces people off their land and away from lifestyles that defined their societies since time immemorial and into hyper-urbanized and condensed settings where organic cultural expression is severely, often intentionally, curtailed. When this happens, it tends, in part, to destroy a people.

Sadly though, there is little international sympathy for wartime attacks on culinary heritage. When it comes to food and war, governments and global institutions like the UN have historically promoted “food security,” roughly defined as a refugee having regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for an active and healthy life. This is crucial live-saving work, but it overlooks that the ability to practice one’s culture as fully as possible is also a means to survival, not just for a person, but also their people.

So I’ve learned how powerful food is. I came to understand how important cooking and cooking one’s own food in the time of crisis is not only just a way of keeping one’s cultural life. It’s an act of defiance and an act of resistance in the face of getting the shit kicked out of you by someone, right? It is like: “You kill us with guns, but I’m going to survive by cooking.” It’s so amazing to me.

Mecca: It is truly amazing.

Michael: It’s super amazing to see this. It’s not like a trite thing. It’s a very important and powerful thing to see a cook— a home cook— women, most often, fighting to find the ingredients to build a dish so their children can know the taste of home. It’s like a hydraulic to memory that is being imparted into the next generation in order to reseed it. That is a powerful way of resisting and fighting back. It’s defiance and resilience. The lessons that are in this book could be applied to how we approach the political, social and cultural crises we have in the United States so that we can get through it.

Mecca: It’s always so fascinating to me as I meet these really amazing women, and we do the cooking together, and I try to tease out some kind of a story. The women who have been through the most shit are the women who are the least likely talk to you about those things verbally. They’re only going to cook for you, and they’re just going to be like, “Here’s the food. Take from what you can,” you know.

“In this dish is everything that you need to know.”

Click here to buy Michael’s book The Last Sweet Bite.

Watch for Alyssa’s contribution to this conversation coming soon!